ประโยชน์ของธาตุเหล็ก

ประโยชน์ของธาตุเหล็ก ในร่างกายของคนเรา จะมีหน้าที่สำคัญดังต่อไปนี้

1.ประโยชน์ของธาตุเหล็ก ทำหน้าที่ในการรวมตัวเข้ากับ วิตามินบี 6 โปรตีนและ ทองแดง เพื่อสร้างเฮโมโกลบินขึ้นมา โดยสารชนิดนี้จะทำหน้าที่ในการส่งออกซิเจนในเลือดจากปอดไปยังอวัยวะต่างๆ ในร่างกายที่ต้องการออกซิเจนและนำเอาคาร์บอนไดออกไซด์กลับเข้ามาสู่ปอดเพื่อทำการขจัดทิ้งออกจากร่างกายผ่านการหายใจต่อไป เพราะฉะนั้นจึงอาจจะกล่าวได้ว่าธาตุเหล็กเป็นตัวช่วยในการสร้างคุณภาพของเลือดและเพิ่มภูมิต้านทานให้กับร่างกาย เพื่อให้ห่างไกลจากโรคต่างๆ ได้นั่นเอง และนอกจากการสร้างเฮโมโกลบินในเลือดแล้ว ประโยชน์ของธาตุเหล็ก ก็ยังช่วยสร้างไมโอโกลบินในกล้ามเนื้ออีกด้วย โดยสารตัวนี้ก็จะช่วยส่งออกซิเจนไปยังกล้ามเนื้อ เพื่อให้กล้ามเนื้อมีการหดตัวตามปกติ และนำเอาคาร์บอนไดออกไซด์ออกมาเพื่อกำจัดทิ้งเช่นกัน

2.ทำหน้าที่เป็นส่วนประกอบของโปรตีนและน้ำย่อยอีกหลากหลายชนิด เพื่อกระตุ้นการเจริญเติบโตและกระบวนการหายใจของเซลล์ให้ดีขึ้น โดยโปรตีนที่มีธาตุเหล็กผสมอยู่ได้แก่ ไมโอโกลบิน เฮโมซิเดอริน และเฮโมโกลบิน เป็นต้น ส่วนน้ำย่อยที่มีธาตุเหล็ก ได้แก่ รีดักเทส แคแทเลสและสารต่างๆ เป็นต้น นอกจากนี้ร่างกายของคนเราก็สามารถใช้ประโยชน์ได้ทั้งเหล็กที่อยู่ในรูปของเหล็กเฟอริคและเหล็กเฟอรัส แต่จะสามารถใช้ประโยชน์จากเหล็กเฟอรัสได้อย่างมีประสิทธิภาพมากกว่า

การดูดซึมธาตุเหล็กในร่างกาย

สำหรับการดูดซึมธาตุเหล็กในร่างกายของคนเรา โดยปกติแล้วจะสามารถดูดซึมได้ที่ร้อยละ 6-10 ซึ่งหากธาตุเหล็กในร่างกายมีน้อยก็จะมีการดูดซึมได้เพิ่มขึ้นไปอีก เพราะร่างกายมีความต้องการธาตุเหล็กสูงนั่นเอง นอกจากนี้ธาตุเหล็กที่ได้รับจากอาหารประมาณร้อยละ 2-4 จะถูกนำไปใช้ในร่างกายและจะเก็บไว้ที่ม้าม ไขกระดูก เลือดและตับ ซึ่งส่วนใหญ่แล้วผู้ชายจะมีธาตุเหล็กสะสมไว้มาก จึงทำให้ดูดซึมธาตุเหล็กได้น้อย แต่ผู้หญิงจะมีปริมาณธาตุเหล็กสะสม น้อย จึงสามารถดูดซึมธาตุเหล็กได้มากกว่านั่นเอง และสำหรับปริมาณของธาตุเหล็กที่ถูกดูดซึมเข้าสู่ร่างกายก็จะขึ้นอยู่กับปัจจัยดังต่อไปนี้

1. ความต้องการเหล็กของร่างกาย ซึ่งหากร่างกายกำลังต้องการธาตุเหล็กสูง ก็จะดูดซึมได้ดีขึ้น โดยเฉพาะในภาวะที่ร่างกายกำลังขาดธาตุเหล็กหรือร่างกายมีความต้องการธาตุเหล็กมากกว่าปกติ เช่น หญิงตั้งครรภ์ ขณะให้นมบุตรและในเด็กที่อยู่ในวัยกำลังเจริญเติบโต ซึ่งโดยปกติแล้วในภาวะนี้ร่างกายจะทำการดึงเอาธาตุเหล็กจากทรานส์เฟอร์รินมาใช้ก่อน แล้วจึงค่อยดูดซึมธาตุเหล็กเข้าไปทดแทนในภายหลัง ดังนั้นในช่วงภาวะดังกล่าวจึงต้องทานอาหารที่มีธาตุเหล็กให้มากขึ้นนั่นเอง อย่างไรก็ตามกลไกในการดูดซึมเหล็กก็จะทำหน้าที่ป้องกันไม่ให้เกิดการดูดซึมธาตุเหล็กที่มากเกินไปด้วย เพราะอาจจะทำให้เป็นพิษต่อร่างกายได้นั่นเอง

2. สภาพของลำไส้ โดยพบว่าหากลำไส้เล็กตอนบนและกระเพาะอาหารมีสภาวะเป็นกรดก็จะทำให้ร่างกายสามารถดูดซึมธาตุเหล็กได้มากขึ้น เนื่องจากเหล็กเฟอริคจะถูกเปลี่ยนเป็นเหล็กเฟอรัสที่สามารถละลายได้ง่ายและทำให้ง่ายต่อการดูดซึมอีกด้วย ในขณะเดียวกันหากมีการผ่าตัดเอาส่วนใดออกไป ทำให้การผลิตกรดด้อยลง ก็จะทำให้การดูดซึมธาตุเหล็กด้อยลงไปด้วย นอกจากนี้ในส่วนของลำไส้เล็กตอนกลางและตอนปลายจะมีความเป็นด่างมากกว่า จึงทำให้ในส่วนนี้สามารถดูดซึมธาตุเหล็กได้เพียงเล็กน้อยเท่านั้น

3. ส่วนผสมที่อยู่ในอาหารที่บริโภค โดยพบว่าร่างกายของคนเราจะสามารถดูดซึมธาตุเหล็กที่ได้จากเนื้อสัตว์มากถึงร้อยละ 10-30 ในขณะที่ดูดซึมธาตุเหล็กจากผักได้แค่ร้อยละ 2-10 เท่านั้น ยกตัวอย่างเช่น เหล็กที่อยู่ในถั่วเหลือง จะดูดซึมได้ร้อยละ 7 และเหล็กที่อยู่ในข้าวจะดูดซึมได้ร้อยละ 1 เป็นต้น

4. ผลไม้ที่มีกรด โดยพบว่าจะสามารถดูดซึมธาตุเหล็กได้ดีเหมือนกัน ซึ่งกรดที่พบในผลไม้เหล่านี้ได้แก่ กรดมาลิก กรดซิตริกและกรดทาร์ทาริก เป็นต้น

เพราะอะไรเหล็กจากแหล่งพืชจึงดูดซึมได้น้อย?

สาเหตุที่ทำให้ร่างกายสามารถดูดซึมธาตุเหล็กจากแหล่งพืชได้น้อย นั่นก็เพราะ

1. ธาตุเหล็กที่อยู่ในแหล่งพืชส่วนใหญ่จะเป็นชนิดที่ไม่ได้อยู่ในรูปของฮีม จึงทำให้ดูดซึมได้ยากกว่าเนื้อสัตว์ที่มีเหล็กในรูปของฮีมนั่นเอง แต่ทั้งนี้ก็สามารถที่จะเปลี่ยนเหล็กในรูปของเหล็กเฟอริคในแหล่งพืชให้เป็นเหล็กเฟอรัสที่ดูดซึมได้ง่ายด้วยการดื่มน้ำส้มหลังจากทานอาหารจำพวกพืชเข้าไปนั่นเอง เพราะน้ำส้มจะช่วยเพิ่มประสิทธิภาพในการดูดซึมธาตุเหล็กได้ดี

2. อาหารในแหล่งพืชมักจะมีใยอาหารสูงมาก ซึ่งจะทำให้มีการดูดซึมเหล็กได้ยากกว่าอาหารที่มีใยอาหารน้อย จึงเป็นผลให้ร่างกายดูดซึมธาตุเหล็กจากแหล่งพืชได้ต่ำมากนั่นเอง ดังนั้นผู้ที่ทานมังสวิรัติจึงมักจะมีภาวะขาดธาตุเหล็กได้มากกว่าคนทั่วไป และต้องทานธาตุเหล็กเสริมเป็นหลัก

3. มีแทนนินสูง โดยสารชนิดนี้จะไปทำให้ประสิทธิภาพในการดูดซึมธาตุเหล็กของร่างกายลดน้อยลง ซึ่งก็มักจะพบได้มากในใบชา ใบชะพลูและใบเมี่ยง ดังนั้นจึงมีคำแนะนำไม่ให้ดื่มชาหลังจากมื้ออาหาร เพราะจะทำให้ร่างกายไม่สามารถดูดซึมธาตุเหล็กได้เท่าที่ควรนั่นเอง

4. ไฟเตต จะทำหน้าที่ในการขัดขวางการดูดซึมธาตุเหล็ก ซึ่งจะพบได้มากในพืชตระกูลถั่ว พืชผักทั่วไปและธัญพืช

อย่างไรก็ตาม เมื่อทานพืชผักพร้อมกับเนื้อสัตว์ จะทำให้การดูดซึมธาตุเหล็กดีขึ้น ซึ่งนั่นอาจเป็นเพราะในเนื้อสัตว์มีโปรตีนสูง และกรดอะมิโนที่ปล่อยออกมาจากโปรตีนก็มีฤทธิ์ในการเพิ่มการละลายในธาตุเหล็ก จึงทำให้สามารถดูดซึมธาตุเหล็กได้ง่ายขึ้นนั่นเอง นอกจากนี้อาหารที่มีกรดแอสคอร์บิกและกรดซัคซินิคสูง ก็จะช่วยเปลี่ยนเหล็กเฟอริคให้เป็นเหล็กเฟอรัสที่ดูดซึมมาใช้ประโยชน์ได้ง่ายขึ้นอีกด้วย

การดูดซึมเหล็กจากอาหารต่างๆ

|

ประเภทอาหาร

|

ค่าเฉลี่ยของเหล็กที่ดูดซึมจากอาหาร (ร้อยละ)

|

| ข้าว |

1 |

| ข้าวโพด หรือ ถั่วดำ |

3 |

| ข้าวสาลี หรือ ผักกาดหอม |

4 – 5 |

| ถั่วเหลือง |

7 |

| ปลา |

11 |

| เฮโมโกลบิน |

12 |

| เนื้อวัว หรือ ตับ |

22 |

ปริมาณธาตุเหล็กอ้างอิงที่ควรได้รับประจำวันสำหรับคนไทยวัยต่างๆ

|

เพศ

|

อายุ

|

ปริมาณ

|

หน่วย

|

| เด็ก |

1-3 ปี |

5.8 |

มิลลิกรัม/วัน |

|

4-5 ปี |

6.3 |

มิลลิกรัม/วัน |

|

6-8 ปี |

8.1 |

มิลลิกรัม/วัน |

| วัยรุ่นผู้ชาย |

9-12 ปี |

11.8 |

มิลลิกรัม/วัน |

|

13-15 ปี |

14.0 |

มิลลิกรัม/วัน |

|

16 -18 ปี |

16.6 |

มิลลิกรัม/วัน |

| วัยรุ่นผู้หญิง |

9-12 ปี |

19.1 |

มิลลิกรัม/วัน |

|

13-15 ปี |

28.2 |

มิลลิกรัม/วัน |

|

16 -18 ปี |

26.4 |

มิลลิกรัม/วัน |

| ผู้ใหญ่ผู้ชาย |

19-≥ 71 ปี |

10.4 |

มิลลิกรัม/วัน |

| ผู้ใหญ่ผู้หญิง |

19 – 50 ปี |

24.7 |

มิลลิกรัม/วัน |

|

51- ≥ 71 ปี |

9.4 |

มิลลิกรัม/วัน |

| หญิงตั้งครรภ์ |

ควรได้รับยาเม็ดธาตุเหล็กเสริม |

60 |

มิลลิกรัม/วัน |

| หญิงให้นมบุตร |

ควรได้รับเม็ดธาตุเหล็กจากอาหาร

เนื่องจากไม่มีประจำเดือน จึงไม่สูญเสียธาตุ |

15 |

มิลลิกรัม/วัน |

ปัจจัยที่ขัดขวางการดูดซึมธาตุเหล็ก

สำหรับปัจจัยที่ขัดขวางการดูดซึมธาตุเหล็กของร่างกายได้แก่ แกสโตรเฟอริน ( Gastroferrin ) ซึ่งเป็นโปรตีนชนิดหนึ่งที่จะเข้ามาจับตัวกับเหล็ก จนทำให้เหล็กไม่สามารถถูกดูดซึมเข้าสู่ร่างกายได้ แต่สารชนิดนี้ก็จะมีจำนวนที่น้อยลงในผู้ที่เป็นโรคโลหิตจางอีกด้วย เนื่องจากไม่มีธาตุเหล็กให้จับนั่นเอง และนอกจากนี้ฟอตเฟตและไฟเตต ก็เป็นตัวขัดขวางการดูดซึมเช่นกัน ด้วยการเข้าไปรวมกับเหล็กจนทำให้เหล็กไม่ละลายและไม่สามารถถูกดูดซึมได้ หรือ ภาวะความเป็นด่างในลำไส้ ซึ่งไม่เหมาะกับการดูดซึมเหล็ก ดังนั้นผู้ที่กินยาลดกรดหรือกินอาหารที่มีความเป็นด่างสูงจึงมักจะทำให้ร่างกายได้รับธาตุเหล็กต่ำไปด้วยนั่นเอง และนอกจากปัจจัยดังกล่าวนี้แล้ว การทานอาหารที่มีแคลเซียมสูงและอาหารที่มีธาตุสังกะสีสูง ก็จะไปยับยั้งการดูดซึมของธาตุเหล็กเช่นกัน

การรักษาสมดุลประโยชน์ของธาตุเหล็ก

ร่างกายของคนเราจะมีภาวะที่ต้องรักษาสมดุลของธาตุเหล็กบ่อยครั้ง ซึ่งโดยปกติในวันหนึ่งคนเราจะมีการสูญเสียธาตุเหล็กเป็นพื้นฐานอยู่แล้ว โดยสูญเสียออกไปพร้อมกับเหงื่อ ปัสสาวะและอุจจาระนั่นเอง นอกจากนี้เมื่อเม็ดเลือดแดงหมดอายุ 120 วัน ก็จะเกิดการแตกตัวและถูกทำลายออกไป ส่วนเหล็กที่มีอยู่ก็จะมีการนำไปใช้เพื่อสร้างเม็ดเลือดแดงต่อไป ส่วนในผู้หญิงก็มักจะสูญเสียธาตุเหล็กจากการมีประจำเดือนอยู่เสมอ โดยจะสูญเสียออกมาพร้อมกับเลือดประจำเดือน ซึ่งเฉลี่ยประมาณ 0.5 – 1.0 มก./วันเลยทีเดียว นอกจากนี้ร่างกายของคนเราก็จะมีการเก็บธาตุเหล็กไว้จำนวนหนึ่งเพื่อนำไปใช้ประโยชน์ในยามที่ร่างกายมีความต้องการธาตุเหล็กมากกว่าปกติ เช่น ในช่วงระยะท้ายของการตั้งครรภ์ ช่วงการให้นมบุตร เป็นต้น และในช่วงเวลาดังกล่าวก็จะมีความสามารถในการดูดซึมธาตุเหล็กเพิ่มมากขึ้นกว่าปกติอีกด้วย โดยสำหรับแหล่งอาหารที่ร่างกายมักจะได้รับธาตุเหล็กมากที่สุดก็คือตับและเนื้อสัตว์ ในขณะที่ได้รับธาตุเหล็กจากแหล่งพืชน้อยมาก เพราะในพืชจะมีปัจจัยที่ทำให้การดูดซึมเหล็กเป็นไปได้ยากนั่นเอง

แหล่งอาหารที่พบธาตุเหล็กสูง

แหล่งอาหารที่สามารถพบธาตุเหล็กได้สูง ได้แก่ ตับ เนื้อสัตว์ ไข่แดง เลือด ลูกพรุน ลูกเกด และถั่วเมล็ดแห้ง เป็นต้น โดยเฉพาะใบ ขี้เหล็ก ใบยอและใบชะพลูที่สามารถพบธาตุเหล็กได้มากเป็นพิเศษ ส่วนในนมจะพบธาตุเหล็กได้เพียงเล็กน้อยเท่านั้นและนอกจากธาตุเหล็กจะพบได้จากแหล่งอาหารทั่วไปแล้ว ยังได้จากภายในร่างกายของตัวเองอีกด้วย ด้วยการสลายของเม็ดเลือดและการสลายออกมาจากแหล่งที่เห็บธาตุเหล็กเอาไว้ ทำให้ร่างกายสามารถนำเหล็กที่ได้นี้ไปใช้ประโยชน์ได้นั่นเอง ซึ่งส่วนใหญ่ร่างกายของคนเราจะได้รับเหล็กจากการสลายตัวของเม็ดเลือดแดงที่ประมาณ 20 มก./วัน โดยนอกจากนี้ในหญิงตั้งครรภ์ก็ควรได้รับยาเม็ดธาตุเหล็กเสริมที่ 60 มก./วัน และหญิงให้นมควรได้รับที่ 15 มก./วัน

สาเหตุของการขาดธาตุเหล็ก

โดยจากการศึกษาพบว่าผู้หญิงมักจะขาดธาตุเหล็กได้มากที่สุดและธาตุเหล็กที่ได้รับจากอาหารในแต่ละวันก็มักจะไม่เพียงพออีกด้วย นั่นก็เพราะ

1. มีการสูญเสียเลือดเป็นระยะเวลานาน โดยเฉพาะคนที่มีแผลในกระเพาะอาหาร เป็นเนื้องอก เป็นโรคพยาธิปากขอและพยาธิแส้ม้า เป็นริดสีดวงทวารและลำไส้อักเสบเรื้อรัง รวมถึงในคนที่ประจำเดือนมามากกว่าปกติด้วย

2. เกิดความผิดปกติในการดูดซึม จึงทำให้ร่างกายดูดซึมธาตุเหล็กได้น้อยกว่าปกติ เป็นผลให้ได้รับธาตุเหล็กไม่เพียงพอ โดยเฉพาะในคนที่เป็นโรคอุจจาระร่วง

3. ร่างกายไม่สามารถที่จะนำเหล็กที่ดูดซึมไปใช้ประโยชน์ได้ ซึ่งอาจเป็นผลมาจากการที่ร่างกายขาด แร่ธาตุทองแดง วิตามินเอ หรือเป็นโรคเลือดบางชนิด

4. อยู่ในภาวะที่ร่างกายมีความต้องการเหล็กมากกว่าปกติ เช่น ในช่วงตั้งครรภ์ ให้นมบุตร และเด็กที่อยู่ในวัยเจริญเติบโต ซึ่งจะต้องการธาตุเหล็กสูงมาก

5. การสะสมของเหล็กมีน้อยตั้งแต่กำเนิด ส่วนใหญ่จะเกิดกับเด็กแฝดหรือเด็กที่คลอดก่อนกำหนดนั่นเอง

6. ได้รับอาหารที่มีธาตุเหล็กต่ำหรือธาตุเหล็กอยู่ในสภาพที่ร่างกายไม่สามารถดูดซึมได้ หรือดูดซึมได้ยากมาก

7. ได้รับการผ่าตัดกระเพาะอาหาร ซึ่งจะทำให้ประสิทธิภาพในการดูดซึมธาตุเหล็กน้อยลงไปด้วย

ผลของการขาดธาตุเหล็ก

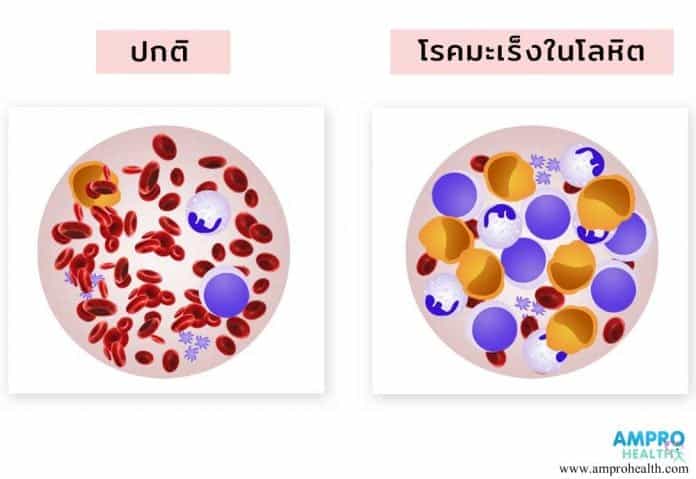

เมื่อร่างกายขาดธาตุเหล็กจะส่งผลกระทบมากพอสมควร โดยกรณีที่ขาดธาตุเหล็กเพียงเล็กน้อย จะทำให้ความสามารถในการทำงานของอวัยวะต่างๆ ในร่างกายลดน้อยลง เป็นผลให้เด็กมีการเจริญเติบโตช้ากว่าปกติ มีภูมิคุ้นกันโรคต่ำและอาจเจ็บป่วยด้วยโรคต่างๆ ได้ง่าย ทั้งยังบั่นทอนพัฒนาการ การเรียนรู้ของเด็กทารกอีกด้วย ส่วนในคนที่ขาดธาตุเหล็กมากๆ จนถึงขั้นมีอาการเลือดจางแบบเรื้อรัง ก็มักจะมีอาการเหนื่อยง่าย ปวดศีรษะบ่อยๆ เบื่ออาหาร อ่อนเพลีย หายใจลำบาก ใจสั่น จุกเสียดบริเวณยอดอกบ่อยๆ เล็บและลิ้นซีด บวมตามข้อเท้า นอกจากนี้ก็อาจมี อาการมือและเท้าชาและเจ็บเสียวตามมือตามเท้าได้เหมือนกันโดยนอกจากอาการดังกล่าวแล้ว สำหรับบางคนก็อาจมีอาการแสบปาก แสบลิ้น มุมปากเปื่อย กลืนอาหารลำบาก คล้ายกับขาด วิตามินบีสอง ได้อีกด้วย และสำหรับผู้หญิงบางคนก็อาจจะมีปัญหาระดูมาผิดปกติ มาไม่ตรงกำหนดหรือมาน้อยจนเกินไป หรือในคนที่ขาดธาตุเหล็กอย่างรุนแรงก็จะมีอาการที่รุนแรงขึ้น และเล็บอาจแบนและงอนขึ้นอย่างเห็นได้ชัดเลยทีเดียว และที่น่ากลัวที่สุดก็คือ เมื่อเม็ดเลือดแดงมีสีซีดกว่าปกติ จะทำให้เฮโมโกลบินลดลง เป็นผลให้ขนากของเม็ดเลือดแดงเล็กลงมาก จนทำให้ไม่สามารถนำพาออกซิเจนไปยังส่วนต่างๆของร่างกายได้อย่างมีประสิทธิภาพ ซึ่งก็จะทำให้ร่างกายมีความอ่อนเพลียผิดปกติ ผิวหนังเหี่ยวย่น ซีดเหลือง หัวใจโต สติปัญญาเริ่มเลอะเลือน และมีอาการบวมทั้งตัวอย่างเห็นได้ชัด ซึ่งก็อันตรายมากทีเดียว

การรักษาโรคเลือดจางจากการขาดธาตุเหล็ก

สำหรับการรักษาโรคเลือดจางจากการขาดธาตุเหล็ก จะต้องดูจากสาเหตุเพื่อจะได้รักษาได้ถูกทางมากขึ้น เช่นหากเป็นโรคเลือกจางจากการที่ร่างกายสูญเสียเลือดเป็นเวลานานหรือเป็นโรคระบบทางเดินอาหารที่ทำให้การย่อยอาหารไม่ดีและส่งผลให้เกิดการดูดซึมธาตุเหล็กได้น้อย ก็จะต้องทำการรักษาให้หายขาด และตามด้วยการเสริมธาตุเหล็กเพื่อปรับสมดุลของเม็ดเลือดอีกครั้ง ส่วนผลเสียของการที่ร่างกายขาดธาตุเหล็กก็แบ่งออกได้เป็น 6 ข้อดังนี้

1. ผลเสียในหญิงตั้งครรภ์ พบว่าจะทำให้เสี่ยงต่อการเสียชีวิตของทารกในครรภ์และทำให้คลอดก่อนกำหนดได้ ทั้งยังทำให้ทารกที่คลอดออกมาอาจมีภาวะธาตุเหล็กสะสมมาต่ำจนทำให้เจ็บป่วยและเสี่ยงเสียชีวิตในวัยทารกได้เช่นกัน และนอกจากนี้ก็เป็นการเพิ่มอัตราการเสียชีวิตของมารดาในขณะตั้งครรภ์อีกด้วย

2. เป็นผลให้ประสิทธิภาพในการทำงานของอวัยวะต่างๆ ภายในร่างกายด้อยลง เพราะไม่สามารถนำออกซิเจนไปเลี้ยงส่วนต่างๆ ของร่างกายได้อย่างทั่วถึง

3. ทำให้เด็กในวัยเติบโตมีการเรียนรู้ที่ต่ำกว่าปกติ และอาจมีพฤติกรรมแปลกๆ รวมถึงมีอาการเซื่องซึมไม่ค่อยกระตือรือร้นเหมือนเด็กทั่วไปอีกด้วย

4. มีภูมิต้านทานโรคต่ำ ทำให้เสี่ยงต่อการติดเชื้อได้ง่าย โดยเฉพาะการติดเชื้อของระบบทางเดินหายใจส่วนต้น

5. ร่างกายสามารถต้านทานต่ออากาศหนาวเย็นได้น้อยลง และมักจะมีอาการหนาวสั่นได้ง่าย

6. น้ำย่อย อับฟากลี-เซอรอลฟอสเฟตดีฮัยโดรจีเนส ต่ำลง จึงทำให้ประสิทธิภาพในการทำงานของกล้ามเนื้อแย่ลงไปด้วย

และนอกจากนี้หากร่างกายได้รับธาตุเหล็กมากเกินไปก็จะส่งผลเสียได้เช่นกัน โดยเฉพาะผู้ที่ทานธาตุเหล็กเสริมในรูป ของแคปซูลหรือเม็ด โดยในเด็กอาจมีอาการท้องเสีย อาเจียนและอาจถึงขั้นเสียชีวิตได้ ส่วนในผู้ใหญ่ก็อาจมีอาการท้องผูก คลื่นไส้อาเจียน ได้เช่นกันโดยเมื่อปี พ.ศ.2547 ก็ได้มีการออกมาประกาศเตือนจากเอฟเอสเอว่า การได้รับธาตุเหล็กมากกว่า 17 มิลลิกรัมต่อวันจะทำให้เกิดอาการปวดท้องและอาจท้องร่วงได้ แต่เมื่อหยุดรับประทานธาตุเหล็ก อาการเหล่านี้ก็จะค่อยๆ หายไปเอง อย่างไรก็ตามเพราะร่างกายไม่สามารถกำจัดธาตุเหล็กส่วนเกินออกจากร่างกายได้นอกจากมีการเสียเลือด ดังนั้นจึงควรทานธาตุเหล็กอย่างพอเหมาะ และนอกจากนี้ก็พบอีกว่าการได้รับธาตุเหล็กมากเกินไป จะทำให้เสี่ยงต่อการเป็นโรคหัวใจและโรคมะเร็ง รวมถึงเกิดความผิดปกติบางอย่าง และยังเสี่ยงต่อภาวะตับแข็งที่เป็นอันตรายมากอีกด้วย ส่วนวิธีการรักษาเมื่อร่างกายมีเหล็กเกินก็อาจจะต้องใช้วิธีการปลูกถ่ายไขกระดูก ฉีดยาเพื่อนำธาตุเหล็กออกมาหรือกินยาเพื่อขับธาตุเหล็กเลยทีเดียว

อ่านบทความที่เกี่ยวข้องเพิ่มเติมตามลิ้งค์ด้านล่าง

เทคโนโลยีช่วยการเจริญพันธุ์ในปัจจุบันมีให้เลือกหลากหลายวิธี แต่หนึ่งในวิธีที่ได้รับความนิยมและถูกเลือกใช้บ่อยที่สุด โดยเฉพาะในกรณีที่ฝ่ายชายมีปัญหาเรื่องอสุจิก็คือการทำ ICSI ด้วยเทคนิคการฉีดอสุจิที่คัดเลือกแล้วเข้าไปในไข่โดยตรง ทำให้ ICSI จึงกลายเป็นความหวังของคู่รักหลายคู่ที่อยากมีลูก

เทคโนโลยีช่วยการเจริญพันธุ์ในปัจจุบันมีให้เลือกหลากหลายวิธี แต่หนึ่งในวิธีที่ได้รับความนิยมและถูกเลือกใช้บ่อยที่สุด โดยเฉพาะในกรณีที่ฝ่ายชายมีปัญหาเรื่องอสุจิก็คือการทำ ICSI ด้วยเทคนิคการฉีดอสุจิที่คัดเลือกแล้วเข้าไปในไข่โดยตรง ทำให้ ICSI จึงกลายเป็นความหวังของคู่รักหลายคู่ที่อยากมีลูก ก่อนตัดสินใจทำ ICSI หลายคนอาจสงสัยว่ากระบวนการนี้ต้องทำอะไรบ้าง มีความยุ่งยากมากแค่ไหน ซึ่งจริง ๆ แล้วการทำ ICSI มีลำดับขั้นตอนที่ชัดเจนและไม่ยุ่งยากอย่างที่หลายคนกังวล โดยลำดับขั้นตอนการทำ ICSI มีดังนี้

ก่อนตัดสินใจทำ ICSI หลายคนอาจสงสัยว่ากระบวนการนี้ต้องทำอะไรบ้าง มีความยุ่งยากมากแค่ไหน ซึ่งจริง ๆ แล้วการทำ ICSI มีลำดับขั้นตอนที่ชัดเจนและไม่ยุ่งยากอย่างที่หลายคนกังวล โดยลำดับขั้นตอนการทำ ICSI มีดังนี้

วัตถุเจือปนอาหารจะมีหลากหลายชนิดด้วยกัน ซึ่งบางชนิดก็อาจเป็นอันตรายต่อสุขภาพในระยะยาวได้ นั่นก็คือวัตถุเจือปนอาหารที่เป็นสารเคมีโดยถูกสังเคราะห์ขึ้นมานั่นเอง ดังนั้นก่อนจะเลือกซื้อ อาหารแปรรูป ต่างๆ จึงควรทำความเข้าใจเกี่ยวกับวัตถุเจือปนในอาหารแปรรูปได้ดี เพื่อจะได้ไม่ก่อให้เกิดอันตรายต่อสุขภาพ

วัตถุเจือปนอาหารจะมีหลากหลายชนิดด้วยกัน ซึ่งบางชนิดก็อาจเป็นอันตรายต่อสุขภาพในระยะยาวได้ นั่นก็คือวัตถุเจือปนอาหารที่เป็นสารเคมีโดยถูกสังเคราะห์ขึ้นมานั่นเอง ดังนั้นก่อนจะเลือกซื้อ อาหารแปรรูป ต่างๆ จึงควรทำความเข้าใจเกี่ยวกับวัตถุเจือปนในอาหารแปรรูปได้ดี เพื่อจะได้ไม่ก่อให้เกิดอันตรายต่อสุขภาพ วัตถุเจือปนอาหารส่วนใหญ่มักจะผ่านการอนุญาตแล้ว แต่ต้องใช้ในปริมาณที่กฎหมายกำหนด เพื่อไม่ให้เกิดอันตรายต่อสุขภาพร่างกาย โดยมีประเภทของวัตถุเจือปนอาหารดังนี้

วัตถุเจือปนอาหารส่วนใหญ่มักจะผ่านการอนุญาตแล้ว แต่ต้องใช้ในปริมาณที่กฎหมายกำหนด เพื่อไม่ให้เกิดอันตรายต่อสุขภาพร่างกาย โดยมีประเภทของวัตถุเจือปนอาหารดังนี้

สำหรับประโยชน์และคุณสมบัติของเบตาเลน ( Betalain ) ในแก้วมังกรพบว่า

สำหรับประโยชน์และคุณสมบัติของเบตาเลน ( Betalain ) ในแก้วมังกรพบว่า โดยจากความเชื่อดังกล่าวก็ได้มีการศึกษาและพบว่าจริงๆ แล้วเบตาเลนมีโครงสร้างที่แตกต่างจากสารให้สีชนิดอื่นๆ อย่างสิ้นเชิง โดยจะมีความคล้ายกับโปรตีนมากกว่าสารให้สี เพราะมีธาตุไนโตรเจนเป็นส่วนประกอบ นอกจากนี้ก็สามารถแบ่งออกได้เป็น 2 กลุ่มใหญ่ๆ ตามลักษณะการให้สีของเบตาเลนและคุณสมบัติที่พบ ซึ่งได้แก่

โดยจากความเชื่อดังกล่าวก็ได้มีการศึกษาและพบว่าจริงๆ แล้วเบตาเลนมีโครงสร้างที่แตกต่างจากสารให้สีชนิดอื่นๆ อย่างสิ้นเชิง โดยจะมีความคล้ายกับโปรตีนมากกว่าสารให้สี เพราะมีธาตุไนโตรเจนเป็นส่วนประกอบ นอกจากนี้ก็สามารถแบ่งออกได้เป็น 2 กลุ่มใหญ่ๆ ตามลักษณะการให้สีของเบตาเลนและคุณสมบัติที่พบ ซึ่งได้แก่ ในบางคนที่เคยกินแก้วมังกรแล้วปัสสาวะออกมาเป็นสีแดงก็อาจเกิดความสงสัยว่าเป็นเพราะอะไรและผิดปกติไหม ซึ่งสรุปได้ว่าอาการดังกล่าวเป็นเรื่องปกติ ไม่อันตรายและไม่ต้องกังวลใดๆ เพราะในแก้วมังกรมีเบตานินสูงมากและเนื่องจากร่างกายไม่สามารถย่อยสารสีดังกล่าวได้ จึงต้องขับออกมาพร้อมกับปัสสาวะ เป็นผลให้ปัสสาวะมีสีแดงนั่นเอง เพราะฉะนั้นจึงวางใจได้เลยว่าไม่ใช่อาการผิดปกติใดๆ แน่นอน

ในบางคนที่เคยกินแก้วมังกรแล้วปัสสาวะออกมาเป็นสีแดงก็อาจเกิดความสงสัยว่าเป็นเพราะอะไรและผิดปกติไหม ซึ่งสรุปได้ว่าอาการดังกล่าวเป็นเรื่องปกติ ไม่อันตรายและไม่ต้องกังวลใดๆ เพราะในแก้วมังกรมีเบตานินสูงมากและเนื่องจากร่างกายไม่สามารถย่อยสารสีดังกล่าวได้ จึงต้องขับออกมาพร้อมกับปัสสาวะ เป็นผลให้ปัสสาวะมีสีแดงนั่นเอง เพราะฉะนั้นจึงวางใจได้เลยว่าไม่ใช่อาการผิดปกติใดๆ แน่นอน